It is our inward journey that leads us through time—forward or back, seldom in a straight line, most often spiraling. Each of us is moving, changing, with respect to others. As we discover, we remember; remembering, we discover; and most intensely do we experience this when our separate journeys converge.

—Eudora Welty, One Writer’s Beginnings

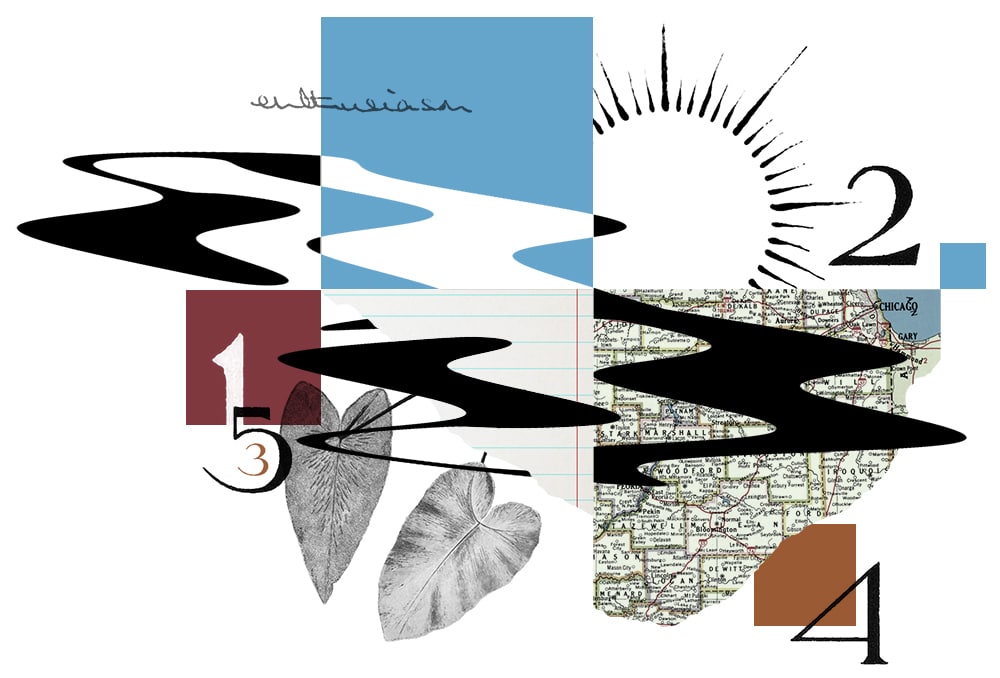

1.

I have been babysitting my student’s two-year-old boy for the last three hours, while my student and his wife go out for the night. The boy is bubbly. He has the habit of bouncing on his toes when he is excited, and he is excited about everything. He’s discovered language, and I marvel at how his mouth and tongue wrestle with words. His vocabulary grows by the hour. He has devoured the words I’ve taught him—predicament, osmosis, malfunction. As in, “We have a predicament here, young boy.” And, “You’re learning through osmosis.” And, “The robot has a malfunction.” His comprehension and formation of language fascinate me to no end. I tell him in the most excited voice I can muster how smart he is. He’s excited at my excitement, so he speaks with more vigor. Puts words into unique orders. Forms complicated and syntactically incorrect sentences. He trips up when he says grasshopper (“hassgropper”) and lemonade (“lemonlaid”) and flip-flops (“footlops”). The two words he knows well, the two words he uses over and over, are why and what. When I lay him down to tell him a bedtime story, he interrupts with questions. These questions are philosophical and illogical in the best ways. Why? he wants to know. Why does the hedgehog have needles? Why is the prince so angry? And soon my story, a loosely planned narrative, derails. And soon we are off into avenues of more interest. More inquiry. Finally he succumbs to sleep, but we never reach the end of the story.

2.

I can’t write a chronological career narrative for this Guggenheim Fellowship, not because it is beneath me, or because I don’t believe in career narratives, but because I’m unsure where to start and where to end. Every time I think of beginnings and endings, I think of death, a dark hole I plummet down.

3.

In this time of my life—after a breakup, in the long trench of middle age—I know only disorder, clutter, chaos. This is my writing process. I am not the Pulitzer Prize–winning author Adam Johnson, who logs where, when, and how much he writes, into spreadsheets that compute his optimal places and times for creativity. I’m not like my colleague, the novelist John Henry Fleming, who wakes at four in the morning and pounds out ten pages before his kids wake up for school and it is time for carpooling.

No. I write amid mess. I have an office, but it’s a storage facility for shoes and unmatched socks.

Right now, I’m in the kitchen with my partner’s family. It’s evening. Her younger daughter is playing The Sims on the computer, controlling the destinies of her created characters. Her older daughter is busy making shepherd’s pie for dinner. My partner is tending to a sick pet cockatiel. In the middle of this is me, writing a career narrative for a fellowship I’m afraid I’m not good enough to get.

4.

My creative nonfiction students believe the material for their nonfiction writing exists only in the time period they have been alive in the world. The questions they ask limit them to—well—them. Their narrow perspectives hinder the scopes of their narratives. I want them to remember a time when the world was new, remember that boy or girl wrestling with language for the first time, questioning everything. When they—we—were young, the outside world was one big fascination. I prod them to dig deeper, to open other doors they never knew existed, to explore other possibilities, to see themselves before their births, to see themselves after they expire, to see themselves beyond themselves.

I was like them. (Still am at times.) As a nineteen-year-old English major at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, studying fiction and nonfiction with Kent Haruf and Lisa Knopp, I turned in terribly young stories about greenish aliens that resembled Asians or—although I was Buddhist—about God. I used to believe that telling a personal story was all you needed in narrative, that the story would do the work, that plot alone was power. My youth made me dream, and I dreamt for myself a career similar to that of Amy Tan (the only Asian-American writer I knew back then, and the inspiration for my collegiate nom de plume, Pierce Tan: Tan after Amy; Pierce because my stories would pierce your soul). Like Amy, I would write a bestseller. I would write and write and write. I would be famous.

This imagined writing career was a story marked by monumental accomplishments. What it lacked was the what and the why and the how. What it lacked was “the guts,” as a teacher of mine once told me. What it lacked was an understanding that being a writer is not a career choice at all, but a devotion to engage in the life of the mind, in the creation of art that seeks to delve deep beneath the surface.

5.

It would be easy to say my writing career began when my Thai immigrant parents came to America—my mother in 1968, my father in 1972. It would be easy to say it began when I was born in 1976, a couple of weeks before the bicentennial. Or it began when I fell from the high chair and broke my arm. Or when a group of bullies pinned me down and slapped my belly pink and raw. Or when my mother went in for an emergency hysterectomy. Or when my father moved out and disappeared for two years. But none of this would be true. These are markers of my life. They are like the long drives on I-57 I used to make from southern Illinois up to Chicago. The land would undulate up and down, then flatten out to miles and miles of agriculture. I knew I would pass Mt. Vernon, then Effingham, then Champaign, then Kankakee, and then finally reach Chicago. Within those six hours, my mind would jump back and forth between ideas, girls, classes, life and death.

Perhaps it is much simpler.

Perhaps my writing career began when I asked my first question.

6.

Or sooner.

Buddha said in this life we look for our fingerprints from our other lives.

7.

The immigrant story is not linear. It is not shaped by cause and effect as media outlets make it out to be. And the immigrant story is not finite; it doesn’t end once an immigrant makes it to America. It fact, it begins again. It keeps beginning. There are other challenges. Other heartbreaks. Other sadnesses that lurk in the shadows.

The son of immigrants will inherit the immigrant story. At first, he may not know what to do with it. It is heavy and unwieldy. It does not fit comfortably into the pockets of his stonewashed jeans. For a while, he simply finds a place where it can gather dust while he cruises around the mall with his friends. Years later, he will return to it because, eventually, the immigrant story will call to him. He will look at it and see himself. So he will begin to unfold the narrative. Slowly. As he did with paper airplanes to understand the mechanics of their glide. He will not know what to do with what he finds. There are too many questions. Too many avenues of exploration. But he will be glad he has found it. All these layers. He has learned that not all questions need answers. Just asking is good enough.

8.

Don’t laugh. The first story I completed was entitled “Murder from the Heart.” It was a mystery set in a high school chemistry class. I don’t remember much of the plot except for the creative use of a petri dish as a murder weapon and a love story between a Thai main character and a beautiful redhead whom I modeled after my current love interest at the time. Don’t laugh. I remember the fancy font I used, some random cursive that would drive me nuts now as a teacher. I was in high school, and my English teacher wrote something like, I really love your writing, Ira. You remind me of me at your age, so lost in the idea of love. I was. I was a love-crazed teenager. Don’t laugh.

My teacher’s praise for “Murder from the Heart” has stuck with me. His praise was better than the Illinois Arts Council Award (2001), or the Arts and Letters Fellowship (2003), or the New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship (2005), or the Just Desserts Short-Short Fiction Prize (2008), or any of the times my essays have been selected as notable in Best American Essays (1999, 2007, 2008, 2011, 2013, 2014). (As requested in the Guggenheim guidelines: selected awards and honors.) My English teacher was a man I admired very much during a time in my life I thought I’d never get through. (So spurned by life! Oh angsty adolescence!) His comment on my work was a shared moment, a connection, a communication. A career as a writer is not so much about what you’ve accrued from your writing as it is about the conversations you have entered in with it.

“It’s about being part of this tribe,” a friend once said. This has become my mantra.

9.

I’m not against narrative. I love chronology. My first book, Talk Thai: The Adventures of Buddhist Boy, is a narrative about growing up in Chicago. I have written essays and stories and poems adhering to the rules of chronological order. I admire writers who manage linear time well. To write a memoir is to construct something that is unnatural. We take what comes in fragments, and we impose order. In Angle of Repose, Wallace Stegner wrote, “I believe in Time, as [my grandparents] did, and in the life chronological rather than in the life existential.” And I, of course, understand Stegner. I mean, what do we do to understand ourselves? We create a narrative. We tell a story, and in that story, we learn, we change, we teach.

But for some reason, I can’t wrap my brain around writing a career narrative. And perhaps I’m being dense. Perhaps I’m overthinking this. (I really would like this fellowship!) Because I do feel “existential” about it, as if to list awards and honors doesn’t really encapsulate a career. The things that really capture a career are hard to mention. Are the invisible practices a writer/artist/musician does day in, day out. To paraphrase Zora Neale Hurston: the agony of an untold story.

10.

Just a second ago, my partner’s daughter asked if I was writing a poem. I told her I was working on a grant. “Fun stuff,” she said. Her sister, on the couch watching My Little Pony, said she had Googled me. “You’re famous,” she said. Then she said she watched a Facebook clip of me singing karaoke. “They should give you a grant for that.”

11.

One of the assignments I give my students is the two-page autobiography. They have to write their entire lives in that small space. It’s an impossible assignment, and they think I give it to them to torture them. I do. But like all assignments I’ve given, I’ve done it before, myself. I’ve been tortured, too. My two-page autobiography contained all the topics I return to now, will return to for the rest of my writing career: what it means to be the son of two Thai immigrants; what home is; how to maneuver in the world as a big bodied individual. But that assignment—I restarted it endlessly. I cursed my teacher for assigning it. It never seemed right.

This is a good marker of a career as a writer: the number of writing exercises you’ve done in your life. The number of times you’ve felt tortured. The number of times doubt has crept into your psyche. The number of times you’ve pondered how to write this career narrative.

12.

Answer to the last question above: thirty-three.

13.

When I was awarded the Emerging Writer Fellowship from the Writer’s Center in Bethesda (2011), a friend asked me what emerging means. I told him I didn’t know. I told him I had followed the fellowship guidelines, and according to the guidelines, I qualified. He asked me how they chose winners. I told him I didn’t know. Probably a panel of judges. Probably the quality of work. He told me he thought I had already emerged. That there was nothing emerging about me, especially my writing career. The only thing emerging was my belly over my waistline.

14.

I’ve looked up the etymological roots of the word career. (When desperate, look at an Oxford English Dictionary.) In the 1530s, the word career meant “a running, [a]course,” a term that was used to describe the movement of the sun in the sky. Later, as a verb, career meant “to charge (at a [jousting] tournament)” or “to gallop, run, or move at full speed.”

My career is not running at full speed. It is not staying the course. It is meandering here and there. It is stopping to smell the roses. To spin in an open field. To pick flowers along the way. To be easily distracted by the blinding sun or the buzzing bee. Oh, does it smell fresh baked bread in the valley? Oh, did it remember to turn off the stove at home? Oh, does it hear its mother calling from the next mountain?

Go. Whatever direction. Go. Keep moving. Never stop.