“Here,” Dad said, thrusting a .38 Special into my hands. He had agreed to take me shooting, a present for my eighteenth birthday. The .38 was slimmer than the Colt he had handed me first—more of a ladies’ gun, he said. “Hold it out in your right hand below your shoulder and cup the butt with your left hand.” He dragged on an unfiltered Camel as he stepped back. “Bend your knees a little. You want to be steady. Not stiff.”

I nodded and wiped my sweaty palms on my stonewashed denim short shorts, the kind we called Daisy Dukes, before I took hold of the gun for real. It felt smooth, leaden, and compact on my skin, heavier than I anticipated it would be. Holding it, my long, soft hands—flute player’s hands, piano player’s hands, slender like my mother’s hands—felt puny and fey.

“Come on,” he urged. “Give it a try. You said you wanted to do this. Just brace yourself for the kickback.”

I held up the gun like he showed me, the weight of black metal pouring into my palm. In that instant, I got it. The power. Such a strange thing to feel peaceful with.

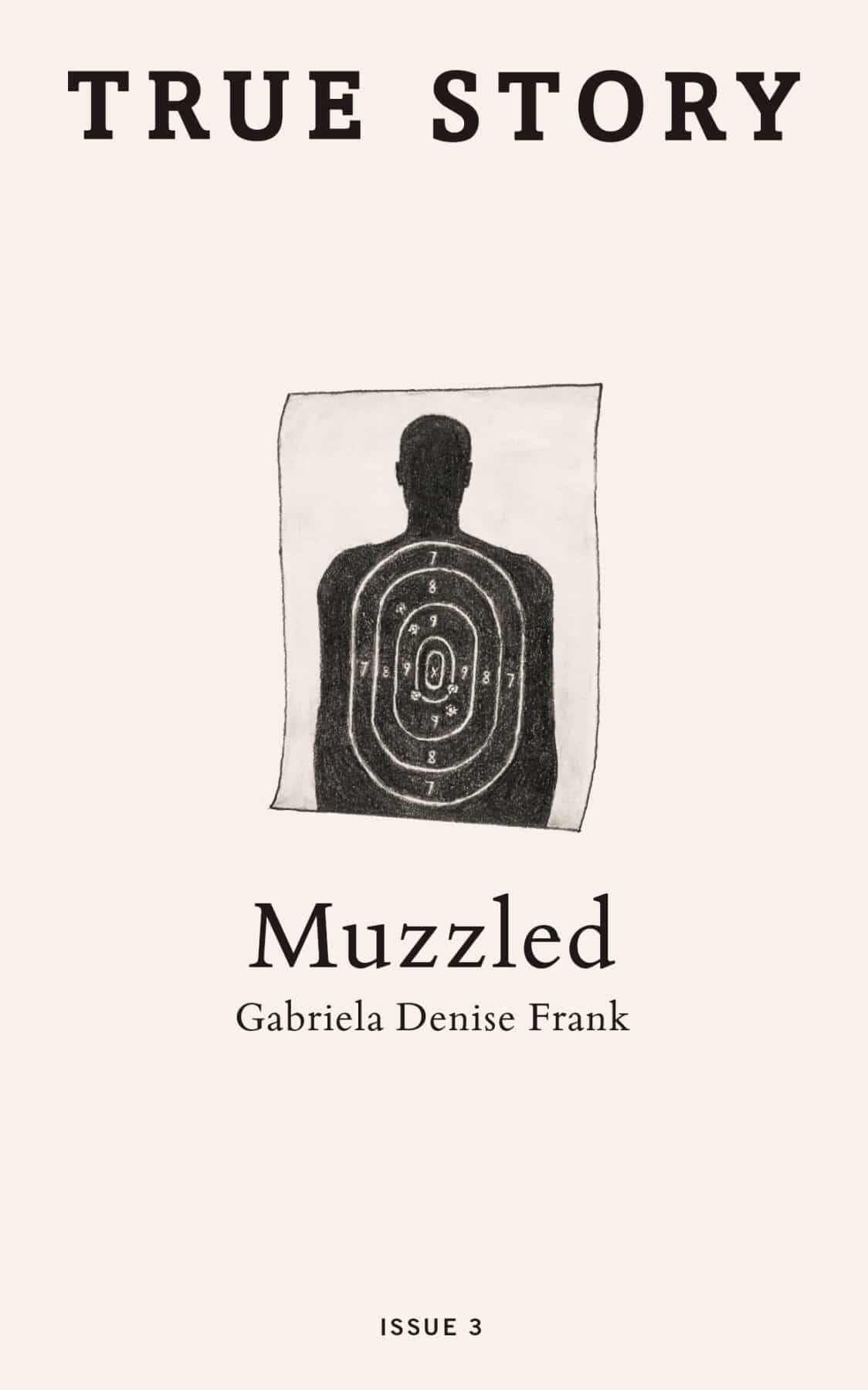

Squinting down the barrel, I found a clear path between the sights into the imagined heart of the paper target flapping many yards out above the gravelly desert floor, above klatches of saguaros shrugging their arms and mounds of stinger-sharp cholla and gnarled clumps of gray-green desert sagebrush. It was past 2:00 p.m.; we had gotten a late start thanks to my birthday buttermilk pancakes, Dad’s specialty.

The July sun glinted off his sunglasses in blinding starbursts; after fifteen minutes of exposure, my bare, freckled shoulders were baking in the 110-degree heat. My father shifted his weight behind me, longing to be somewhere else. I wiggled my thumb to make sure the webbing of my skin was free of the hammer and wouldn’t get caught when it struck.

Instead of the blank face on the target, I imagined my father standing inside the chalk-white outline, his heart slightly off-center. I took a deep breath and aimed for it, his thin, black paper heart.

• • •

Guns, she was reminded then, were not for girls. They were for boys. They were invented by boys. They were invented by boys who had never gotten over their disappointment that accompanying their own orgasm there wasn’t a big boom sound.

Lorrie Moore, “The Jewish Hunter”

• • •

“Remove everything that has no relevance to the story,” Anton Chekhov is famously said to have advised. “If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.” Chekhov surely used the example of a gun because of its power to thrill the reader with nervous anticipation; an inherently dangerous object, it is, by design, created to fire, to harm, to destroy. However, waiting for the gun to go off can distract readers from the rest of the story—for better or worse.

• • •

Some nights, my father chased me into my room, catching me in the final instant before I reached the safety of my bed, which we had tacitly agreed was a free zone. Having caught me, he liked to drag me by my ankles to the living room for “tickle torture,” the cheap synthetic carpet burning the tender white flesh of my stomach. He used his meathooks to flip me over before sitting on top of my tweenage hips, pinning my wrists, delicate as bird bones, above my head. He cackled as I squirmed beneath his callused mechanic’s claws, my heart pumping with fear and anticipation.

Sometimes he’d use my own hands to hit my face. Stop hitting yourself! he’d laugh, swinging my arms at the elbow joints. He couldn’t see that this wasn’t fun for me, that we weren’t playing the same game. The only way to void the play was to go limp and hope that he’d lose interest. Ha! Can’t get away, can you? Aw, come on, gimme a little fight. What’s the matter? Can’t you take a joke? Eventually, I’d cry, and ruin everything. Jesus Christ, stop that. What the hell is your problem? You and your mother, both so goddamned sensitive. Disgusted, he would climb off of me with a push, offended by my swollen face and salty wet cheeks.

Why is it, exactly, that we expect our parents to be better than everyone else? We imagine that our creators owe us a debt—and yet, didn’t they make us for the purpose of being playthings and companions? Don’t we owe them?

My pathetic sobbing grated on Dad’s nerves after a long day in a hot automotive repair garage. All I want is a quiet house, and this is what I get. A mouthy, ungrateful daughter. Get out of here. Oh, you think this is scary? I’ll give you something to be scared about. Go to your room and don’t show your face for the rest of the night. Go! Get out and leave your mother and me alone. Jesus. We can never get any peace.

Children. What ungrateful little fucks we are, each and every one of us.

• • •

People who don’t live at least a little bit in fear, have nothing left to live for.

Dave Matthes, Return to the Madlands

• • •

According to the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, one out of three American homes with kids has a gun in it, and nearly 1.7 million children live in a home with an unlocked, loaded gun. Each year, more than 111,000 people in America are shot. Of that number, more than 17,000 are children and teens. In an average year, 2,624 kids die from gun violence, and more than 14,700 are injured by guns, most often by someone they know.

• • •

When I said I wanted to spend my eighteenth birthday shooting guns, my father didn’t hesitate. My first moments as a full-fledged adult would be spent exercising my Second Amendment rights. He liked shooting so much, he didn’t suspect a thing.

• • •

As time went on, we learned to arm ourselves in our different ways. Some of us with real guns, some of us with more ephemeral weapons, an idea or improbable plan or some sort of formulation about how best to move through the world.

Colson Whitehead, Sag Harbor

• • •

When I was fifteen, our neighbor held his wife at gunpoint during an argument. Their children were away for the evening, sleeping over at friends’ houses. There was no one at home to stop him. When she said that their marriage was over, that she was going to take their kids and leave him due to his abuse, he pulled out a gun and grabbed her, holding the muzzle at her temple. If you go, I go, he swore, his hand trembling; he would kill her first, then himself.

His wife pleaded for her life, quickly reversing everything she had said moments before. She didn’t mean it. They could work it out. Please. Think of the kids. She promised to stay if he let her go. They could remain a family. He didn’t believe her. This went on for hours. Eventually, she persuaded him to allow her to call for help, a mediator to get them both to safety for the sake of their family. He loved them, didn’t he? Slowly, gingerly, he walked with her to the rotary phone in the hallway, his body pressed tight to hers, two bodies dancing. She dialed, his arm wrapped around her, vise-tight. The muzzle of the pistol pressed an O-shaped mark into her flesh when the operator picked up. Nine-one-one, what is the nature of your emergency?

At 1:00 a.m. police cars crowded the mouth of our cul-de-sac. Our house, two doors down, became their base of operations. When the officers assembled outside, the wife turned over the receiver to her husband, and the standoff became a conversation about him. Of course, it had been, all along. Our neighbor talked with the police for hours, sobbing and yelling at the negotiator who bargained for the woman’s freedom.

Around three in the morning, they convinced him to set her free. She was to walk out through the front door, alone and unharmed; whatever problems they had could be worked out in therapy together. That was the deal. Their two-story olive-green cottage sat in the bulb of the cul-de-sac; the cops turned on their white-hot spotlights to light her way. Following their instructions, she stepped slowly and carefully out of the front door in her pink bathrobe, arms high in the air. She tiptoed past the bulletproof-vested cops, their weapons drawn and pointed at the front door and the two picture windows, in case he decided to open fire. After she squatted safely behind the farthest squad car in her slippers, the cops swarmed inside to arrest her husband, who was still in the hallway on the phone. They marched him out with his head down, his wrists shackled in silver cuffs drawn snug behind his back.

My parents told me all this the next morning. Despite the squawking of walkie-talkies, our front door slamming, sirens wailing, I had slept through the whole thing. At fifteen, I could still fall dead asleep. A part of me knew I had time to rest up for the real showdown, the one that would take place cowboy-style between my father and me someday. The inevitability of our match loomed in the distance, angry clouds lurking beneath the sunset. A storm was coming, and there wasn’t a thing any of us could do to stop it.

• • •

“No,” Gideon says. “No guns. The most dangerous weapon you have is your brain. Give someone a gun and they tend to quit using it.”

Paula Stokes, Vicarious

• • •

We had to drive a ways north of Phoenix to reach the shooting range off of New River Road. The dry, dusty ground was painted with purple boulders, orange African daisies, and squat barrel cactus. We drove in Dad’s car, a cherry-red 1976 Pontiac Trans Am that we called “The Bird” for the flaming Firebird decal emblazoned on the hood. He always hated to turn on the AC, so we rolled down the windows and sweated. At lights, he punched the gas, air gusting through the open windows in sharp staccato blasts. I closed my eyes and held on to the panic bar, feeling my hair, a fried Sun-In orange brown, whip the sides of my face. Stop hitting yourself.

Whether he knew it or not, my request to go shooting was as much a fuck you as my way of meeting my father on his ground. It was for this same reason that I had feigned an interest in cars my whole life, an excuse to be close with him, to pepper him with questions—What’s this do? What’s that called?—that he normally wouldn’t tolerate. Leave me alone, I’m busy. When we worked on cars together, he was preternaturally patient, showing me how to do things step-by-step. It turned out that my long, dainty fingers were actually an asset. While I didn’t have his physical strength for leverage and torque, I could worm my digits into nooks and crannies to loosen bolts and ferret out wires, things that were nearly impossible for my father with his thick, oil-stained fingers. Even he saw this advantage.

Given what I was planning, asking him to go shooting with me was less selfish than kind. If you go, I go. After months of hand-wringing, I was ready. It would be over before he knew what had happened. Unlike the past eighteen years, our final moments together would be quick and painless. We’d have this afternoon—a last, fond memory—to reflect on. Guilt and regrets could come later.

• • •

Calculated by dividing the length of one’s index finger—also known as the trigger finger—by the length of the ring finger, finger-length ratio relates to the amount of testosterone available to a fetus in the womb. The results of this indicator are believed by some to be a predictor of physical aggression, even more reliably than an adult male’s level of testosterone.

Funny that, despite the hundreds of times my father laid his hands on me when I was a child, I couldn’t tell you a thing about the length of his fingers. At the time they gripped my skin, I was always too frightened to look.

• • •

We drove for a while on Happy Valley Road, passing whooshing traffic here and there. It was July 3, 1992, a Friday afternoon. Most people had the long holiday weekend off; the few on the road were likely making last-minute trips to the grocery store for forgotten hot dog buns or to the corner stand for sparklers and fireworks before everything closed for Independence Day. In a stretch of empty desert, Dad pulled over onto a dirt road, streams of dust flying behind us like in Smokey and the Bandit, until we slowed at the check-in gate where he paid the owner in cash for using his expanse of desert.

Once going again, we meandered down the dirt road, which had been cleared and graded smooth for vehicle traffic, an anachronistic modernity in what was supposed to be a wild, lawless setting. My father cut the engine when we reached the sign indicating our range.

“You ready?” he said, getting out. He popped open the trunk, where his Winchester and a few handguns were stowed.

I slowly peeled my thighs away from the red vinyl of the bucket seat. I had moved too quickly too many times, chafing my lily-white thighs when I hurried to get out. Even the gentle separation of the two—my skin and the spongy womb of the seat—left an adhesive ache across my flesh, like giant Band-Aids torn off or the stinging memory of my father slapping me across my thighs with his open palm in an effort to quash my acidic sass. Even after years of spankings, he never quite managed to rid me of it.

• • •

The muzzle velocity of a .38 Special Blazer Brass round of ammunition is 865 feet per second, or 590 miles per hour—faster than most commercial airplanes. Prized for its accuracy and easy handling, the .38 Special has remained the most popular revolver cartridge in the world since its introduction more than a century ago. While the .357 Magnum has a sharp and sometimes painful muzzle blast, the .38 Special speaks softly and is considered an excellent choice for new handgun shooters in training.

• • •

During the December 14, 2012, Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, twenty-year-old Adam Lanza fatally shot twenty children and six adult staff using a Bushmaster XM-15 E2S .223-caliber semiautomatic rifle. Prior to driving to the school, Lanza shot and killed his mother with a Savage Mark II .22-caliber rifle, according to media reports. When first responders arrived at the elementary school, Lanza committed suicide by shooting himself in the head with a Glock 20.

On the question of Lanza’s state of mind, the state attorney’s report noted “significant mental health issues that affected his ability to live a normal life and to interact with others, even those to whom he should have been close.”

• • •

My father outfitted me with safety gear: clear plastic goggles to protect my eyes and black, buffered earmuffs that cupped my ears with a strained quiet. He didn’t have any gloves that would fit my hands, so I’d have to be careful about how I held the guns, particularly when I fired. He said that I should expect them to be covered with a sheath of dark powder by the time we finished.

My father placed the adult-sized equipment on my teenage body, his rough, thick fingers grazing my skin. A strange sensation came over me. Was this what Batman felt when he donned his gadgeted superhero suit?

In a display of masculine ease—wordless, squinting—my father squeezed off several rounds with the Colt so I could observe the angle of his arms, the intensity of his aim, his limber yet erect stance. “Watch this,” he said, and aimed again. I could see the ripple of cushioned shock run from the gun through his arms, down his torso, and out of both legs into the desert floor when he fired.

“This one’s got a kick,” he warned, handing over the Colt. “Not sure you can handle it, but let’s give it a try.”

• • •

Tactical defense instructor Greg Ellifritz’s analysis of the .38 Special shows that it takes an average of 1.87 rounds to incapacitate a target. Fifty-five percent of those shot are incapacitated by one shot in the torso or head, while twenty-nine percent of the hits in those same areas are fatal.

• • •

Psychological abuse may be fueled by the parent’s own self-hatred, jealousy, narcissism, or other pathology.

Douglas LaBier, Center for Progressive Development

• • •

Midway through my junior year, I became the one person in a class of five hundred whose mother had died. My friends and schoolmates were instructed by teachers not to talk to me about her death for fear that the subject might upset me. The message was garbled in the transmission, and when I finally returned to school after Christmas break, no one spoke to me at all. I just assumed that everyone hated me.

• • •

“Tighten up your stance,” Dad barked, breaking my concentration. For a second, I fantasized about holding the gun up to his temple like our neighbor had done to his wife. It would scare the shit out of him. For once, I would be holding him, and he would be incapable of doing a goddamned thing about it. That’s what I’d say, too. Try this on for size, Daddy-O. Oh, and by the way, there’s not a goddamned thing you can do about it. His helplessness would make him furious. That’s when I’d cackle. What’s wrong, Spoilsport? I thought we were playing a game.

Or, even better, I’d aim for his heart. Seriously, point-blank. He would misjudge me—too gutless to pull it off—until he looked in my eyes. Either way, he couldn’t call for help. Outside of moguls like Donald Trump, few people had portable cell phones back then; my father certainly didn’t. I’d have to run back to the road, to the guard box, to get help, as I couldn’t drive The Bird. My father said I couldn’t handle the power of his muscle car when I was learning to drive at fifteen, so he never taught me to drive a manual transmission. Those years of not teaching me would serve him right. The hawks and vultures, maybe even a wandering mountain lion, would get to him long before an ambulance arrived. My father’s death would be a tragedy, one on top of another. Poor girl. Last year, her mother dies of cancer at Christmas, and this year, she accidentally shoots her father on her birthday.

I would be consoled. Pitied. No one would suspect me, Miss Goody-Goody, Miss A Student. I would be cared for. Comforted. I would get away with it.

• • •

The guns reminded me that this was just an attempt to punch holes in the darkness that enveloped us now.

Michael Poeltl, The Judas Syndrome

• • •

Even into my late teens, my father made me stand with my hands at my sides before he bent me over to spank me. The station of shame was as essential to the punishment as the spankings themselves. So was the pause before the windup. The fear of knowing that he was about to hit me—whether with the hand or the belt—and wondering how many times and when it would be over drove the physical hurt a shade deeper. The anticipation was sometimes more painful than the actual stings that reddened my flesh.

Look, little girl, you have it coming after trying to pull that shit in my house. Hands by your sides, he’d growl if I raised my hands, even my fingers, in a pathetic attempt to shield my backside. I was to say nothing—not cry, not argue, not protest. After what I’d done, whatever it was, I had it coming. I was to face down, bend over, take it.

• • •

The carpeting in our house was beige, the sort of cheap, low-pile synthetic rug that came standard in our master-planned development. Over time, even with washing, the carpet was a little darker in the high-traffic areas where my father dragged me down the hall. For a period of years, I studied the weave and pile of our carpets regularly, whether from a distance or with my face pressed into it, the weight of his body on mine.

• • •

Anger is an emotional-physiological-cognitive state, whereas aggression is intended harm, such as a verbal attack—insults, threats, sarcasm—or a physical punishment. If permitted an outlet, anger can be expressed, defused, and ultimately resolved through dialogue and reflection. If left unresolved, repressed feelings of anger can lead to physical violence, abuse, and crime, as well as poor physical health and emotional disorders. Like gas under pressure, or a loaded gun, a person simmering with anger is capable of dangerous explosion, often when least expected.

When asked, by Psychology Today, “If you could secretly push a button and thereby eliminate any person with no repercussions to yourself, would you press that button?” more than half of respondents said yes.

• • •

My father was in an unusually good mood on the morning of my birthday. I should have been suspicious, but I let him make pancakes without questioning his benevolence and tried not to slurp my coffee too loud or make chitchat, both of which habits annoyed him. As a reward for my silence, he slid a short stack of perfectly fluffy buttermilk pancakes on my plate.

“When we come back this afternoon, you’d better get to packing,” he said, pouring a second round of batter on the griddle in six small medallions. He and Sandy, my dreaded soon-to-be stepmonster, had put an offer in on a house, a development in their relationship that I was trying to ignore. The worst part wasn’t even the idea of sharing a home with Sandy and her son; it was Dad’s intent to get rid of our house—to wipe the past, the memories of our life with my mother, away. We were scheduled to leave in a few weeks.

“Why can’t we stay here?” I demanded, throwing down my silverware.

“I’ve already told you,” he said. “The house isn’t big enough for all of us.” I knew better. He wanted to erase every last memory of my mother so he didn’t have to think about her; that was why he always slept over at Sandy’s apartment almost every night. My mother’s clothes still hung in her closet.

My eyes narrowed involuntarily and a scowl crept across my face. Too soon! I tried to counsel myself, but he had already caught it. “Watch it, missy,” he warned, pointing the spatula at me after flipping the hotcakes. “I can see what you’re thinking. If you know what’s good for you, you’ll keep it to yourself before you ruin your own birthday.”

I clenched my jaw, hands grasping at my sides, fury about to boil over. I wish it was you who died, an ugly voice inside me sneered. Against my pride, I knew I had to stand down. There’d be time for revenge.

• • •

Perhaps there’s an innate human emotion inside us all that when we are presented with something we don’t understand, we immediately want to kill it.

Todd Berger, Showdown City

• • •

The Columbine High School massacre occurred on April 20, 1999. Seniors Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold murdered twelve students and one teacher and injured twenty-one additional people. Their arsenal included ninety-nine explosive devices in all. Both of the shooters committed suicide: Harris by firing his twelve-gauge Savage-Springfield 67H pump-action shotgun through the roof of his mouth; Klebold by shooting himself in the left temple with his TEC-9 semiautomatic handgun.

Prior to the massacre, both boys were remanded to anger-management classes. Harris also attended psychotherapy after complaining of depression, anger, and suicidal thoughts. Both were said to be academically gifted children who had been victims of bullying for years.

• • •

The fascination of shooting as a sport depends almost wholly on whether you are at the right or wrong end of the gun.

P. G. Wodehouse, “Unpleasantness at Bludleigh Court”

• • •

The speed of a punch has been clocked at thirty-two miles per hour, but it felt more like a bullet whizzing past my head when my dad threw his fist at me several weeks before my birthday. I ducked out of the way, shocked, to find his hand stuck in the drywall. The words we had shot at each other, back and forth, still hung in the air:

“Go on. I’m asking you. Tell me what you think of her,” he said, referring to Sandy.

“You don’t want to know what I think,” I taunted. The ideas that had been curdling inside me for months, confessed in detailed, manic scrawl in my journal, gathered in the back of my throat. I knew I shouldn’t, but I longed to spit them at him.

“Say it. Go ahead. I dare you.” Something inside me was waiting for exactly this moment, an unprecedented opportunity to unleash the barbs of my vengeful lust.

“What do I think of Sandy?” I said in clipped words, blinking. A thin, cold smirk hooked the left corner of my lips. “Since you asked, I think she’s a . . .

“fucking . . .

“bitch!”

The catch of the last syllable was still on my lips at the same moment his fist flew at my head. Later, I realized his swing was exactly the proof I needed. Whatever compact my mother had held him to when she was alive was over; he and I never had such an agreement.

Blood from his knuckles smeared the eggshell-white wall into a meaty pink around the edges of the hole where his hand remained stuck. Startled and exhilarated, I shot back a few paces and flew to my room where I locked the door, waiting for his rage to carry him through it. There! I had said it! I cowered at the head of the bed, the thud of his feet drawing closer in the carpeted hall; he banged on my door loud enough to rattle it in its frame. “Get out here!” he demanded, pounding on the door with each word.

For once, I was too scared to obey him. Instead, I felt an unthinkable hatred—yes, hate—not for my father, but for my mother, whom I had always considered my champion, who had always intervened in our squabbles, who had sat me on her lap to read books, who had whispered nearly every day when she hugged me that she loved me more than anyone. I hated her for marrying him, for being too weak to leave him, for conceding to his rage, for getting sick and dying, and for leaving me alone with him, unprotected.

• • •

Guilt is a sense of responsibility or remorse, while shame is the painful emotion caused by the consciousness of committing a dishonorable action. Although guilt and shame often go hand in hand—the same wrongdoing may give rise to both—the former depends on our capacity for empathy; the latter is an interior reflection. Guilt and shame may also arise from circumstances over which an individual has no control, yet for which she believes herself culpable. Though these feelings have no basis in fact, they are still experienced by the sufferer to the extent she believes herself responsible.

• • •

It’s very dramatic when two people come together to work something out. It’s easy to take a gun and annihilate your opposition, but what is really exciting to me is to see people with differing views come together and finally respect each other.

Fred Rogers, The World According to Mister Rogers

• • •

After 1:00 a.m., a series of small knocks came at my door, which remained locked. Somehow, I had fallen asleep with my arms curled around one of my pillows. “Dee? Are you awake?” Dad said through the door, using my nickname. Was it a trick? After a few minutes, he rapped on he door. “Please. I need your help.” For once, it was a request, not a command.

With sunshade screens permanently screwed to my bedroom window, I was essentially trapped inside; I had to come out of my room at some point, anyway. When he knocked again gently, I padded to my bedroom door and unlocked it. There were impressions in the wood from his banging earlier that evening. I was surprised to find my father’s face ashen, his clenched fists trembling, his eyes unfixed. He had probably drawn on his hidden stash of Vicodin, but it clearly wasn’t enough.

“I think I broke my hand,” he slurred. “Can you drive me to the hospital?” We hadn’t been back to Thunderbird Samaritan since Mom died there, several floors above Urgent Care. I stood dumbly in the doorframe of my room, gazing between his haphazardly bandaged hand and his haggard expression. He wouldn’t make eye contact, though I kept searching his face. “Can you take me?” he said, looking past me into my room, cluttered with half-packing moving boxes. I would never admit it, but I had been dragging my feet intentionally.

“Okay,” I said, bracing for the sucker punch. We took my mother’s car, a maroon Pontiac Grand Prix, which had become mine after she died. It still smelled of her perfume, Chanel No. 5, the one luxury she saved up to buy; there was some left in the bottle, and I had taken to wearing it myself. I shut the driver’s-side door, closing the crisp night air inside the vehicle with us; it triggered a memory of my mother coming home from a PTA meeting wearing her favorite black velour jacket. When I greeted her at the front door with a hug, a wash of sweet-smelling desert night air and perfume surrounded me. I turned over the engine and struggled, yet again, to accept that she wasn’t coming back to save me.

“When the doctors ask how this happened, let me do the talking,” Dad said from the passenger’s seat when the light at Bell Road turned green. At that hour, ours was the lone set of headlights on the road. I nodded, unable to think of a response, and headed south on Forty-Third Avenue. I hit the turn signal before rolling to a stop at Thunderbird, counting one one thousand, two one thousand, like Dad had taught me, as I paused to check for oncoming traffic. We were on the same path I’d taken to visit Mom in the hospital after school every day. Was he thinking about that, too?

“It’s important,” he said, clearing his throat as the glow of yellow-white hospital lights rose ahead. “If they ask you any questions, you have to tell them that you don’t know what happened. You were in your room, okay?”

I shrugged. Yeah. Sure. Whatever.

He added, “If you tell them the truth, they’ll take you away from me.”

Ah. So, he did know.

• • •

Sometimes you have to pick the gun up to put the gun down.

Malcolm X

• • •

On June 12, 2016, Omar Mateen, a twenty-nine-year-old security guard, killed forty-nine people and wounded more than fifty others in an attack on, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida. Mateen, who used a Sig Sauer MCX semiautomatic rifle and a nine-millimeter Glock 17 semiautomatic pistol to carry out the attack at Pulse nightclub, was said to be mentally unstable and deeply disturbed. His ex-wife noted he was often mentally and physically abusive. He was shot and killed by police after a three-hour standoff, according to media reports.

After Mateen was killed, police discovered a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver in his car. The gun was not used in the shooting.

• • •

If someone has a gun and is trying to kill you, it would be reasonable to shoot back with your own gun.

The Dalai Lama

• • •

The Charleston church massacre took place at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church on the evening of June 17, 2015. During a prayer service, twenty-one-year-old Dylann Storm Roof killed nine people with a Glock 41 .45-caliber handgun. According to media reports, he asked one of the survivors, who was physically unharmed, “Did I shoot you?” She replied, “No.” Then, he said, “Good, ’cause we need someone to survive, because I’m gonna shoot myself, and you’ll be the only survivor.” Roof is said to have turned the gun on himself and pulled the trigger, only to realize that it was out of ammunition. He had paused to reload the weapon five times during the attack.

• • •

We do not need guns and bombs to bring peace, we need love and compassion.

Mother Teresa

• • •

The black silhouette on the faraway paper target fluttered in the wind. It could have been any Bad Man slinking through the desert: a terrorist, an intruder, a rapist. All I could see was my father. I held up the gun and found a clear path from the sights straight into his black heart, the one that loved machines and weapons and cars, and Sandy, and certainly my mother, more than me. Yet I couldn’t comprehend the thudding of my own heart. Hating him wasn’t new, nor was wanting to be loved by him, even after everything that had happened. My longing for his approval made me feel vulnerable and sick. After everything he had done to me, how could I desire his affection, his attention, his approval? Why did I care?

I wiggled my thumb to make sure it was free of the hammer. I felt him standing a few paces behind me, his weight pressing my wriggling body to the floor, laughing at my helplessness. That morning, he had wished me happy birthday and signed Love, Dad on the card like he hadn’t slapped me in the face a few weeks before. I could still conjure the sting from his four knobby fingers on the flesh of my face. This would never have happened if my mother had been alive. Or was it unavoidable? Only a matter of time?

Maybe he didn’t mean it. Maybe he hated the weakness in me that reminded him of himself. Maybe he resented me for wearing his genes, his skin, without ever thanking him for my life. Maybe, deep down, even though he wanted to, he knew he couldn’t trust the viper coiled up in her bedroom, pouting behind the locked door. She would never be on his side. From an early age, she struck at him with a poisonous tongue while crying for her mother, always crying, and loving her the best. It was not him, never him, she cried for—never the one who put food on the goddamned table, the one who deserved respect. Even now, when her mother is dead and she has no one else, the girl still can’t offer up the slightest thanks to her father for feeding and clothing her. She asks for things—shoes, books, gas money. Demands them, and expects that they will be given to her. What a spoiled brat. Well, not in my house. If she thinks this is how it’s going to be, she has another think coming. If she thinks she’s too old for me to turn her over my knee, even at eighteen, she’s dead wrong. She’s living under my roof, and she’ll follow my goddamned rules. Just you wait, little girl. If you think this is bad, I’ll give you something to cry about.

• • •

Abuse perverts a child’s innate sense of trust, curiosity, and openness. Over time, repeated abuse intensifies and refracts her reaction to a range of stimuli; her body is a live wire, stripped of its protective casing. When faced with repeated abuse, a child’s physiological responses become commingled into a confounding maze of outrage, hate, shame, vengeance, confusion, and even arousal. In essence, abuse short-circuits the body’s biochemical feedback and sends the inner compass spinning; all interactions, even nonthreatening, present the possibility of peril. In this vulnerable state, the child’s only recourse is to disconnect, go numb—bury her emotions.

• • •

My father saw a lot, but he didn’t seem to notice that I had packed and taped up only a few boxes out of the jumble that littered every surface of my room. He read the scene as the handiwork of a sullen teenager staging a protest, but if he had looked closer, he would have caught that the half-packed open boxes on top were camouflage for a coup.

While he critiqued my stance, my handling of the gun, the cold-blooded killer in me savored the idea that, in a few days, his heart would be shredded, too. I would be out from beneath his thumb. The many times he had reminded me that he was in charge, that he controlled my life, that I had to bend over and take what he was giving me—he would be proven entirely wrong. I could barely conceal my glee.

He had lost my mother, too, he reminded me occasionally. But I never witnessed a familiar sadness or hurt in him, just the inexplicable anger that had always seethed beneath his brow. Maybe, by then, his pain was something that I was blind to. My own was overwhelming; I couldn’t bear giving it more than a momentary thought. Along with my childhood mementos, I shut away my longing for the loving family, the warm and tender father I would never have; my hope, my curiosity, my innate and open trust—these, too, went into a sealed box. Far worse things happen to people every day, I told myself. Your mommy died and your daddy hurts you. Boohoo. Grow up and get over it. But I still wanted him so badly—wanted to throw myself into his arms as much as I wanted to throw him down. I couldn’t see past the twisted mess of my feeings.

“Better grouping of shots this time,” my father said, cutting into my daydream with mild pride after he pulled in the humanoid target, riddled with holes. He had taught me well. Without a word, he secured a fresh sheet inside the metal clips. Then he pressed the switch that drew the target far away on a modified metal clothesline where it flapped in the hot, dry afternoon wind, waiting to be shot. “Go ahead,” he said, glancing down at his watch. We were on borrowed time; since it was my birthday, Sandy had summoned not only him but also me for dinner that night—a meal that was bound to include her signature watery red spaghetti sauce.

I pushed away my acidic distaste and took a deep breath to regain my focus. Soon, they would both be irrelevant.

“Come on,” Dad said, eager to move things along.

I raised the revolver, my frame taut but flexible, and squinted down the sightline. My trigger finger was already sore, but I wasn’t about to admit this. Inside the target, I pictured my father’s face screwed red with rage upon realizing I had left home without his permission. I had tricked him and gotten away with it. Goddamn you. I wasn’t sure if that was his voice or mine. I squeezed the trigger with my trembling finger, relishing the bang and kickback of the shot, square between the eyes. Bang. Bang. Bang. The echo volleyed off the nearby mountains.

The following Monday, without a word, I moved the few items necessary for my survival into my grandmother’s house in Sun City while my father was at work. I left the rest of my boxes, half-packed with childhood memorabilia that I would never see again, along with a note. Judging by the voice mail he left on my grandmother’s machine, we had enraged him with our collusion, our abandonment, our betrayal. How dare we—his own mother and daughter—fucking We stopped the tape before the message was over, and Nanny and I never said it aloud, but we both feared for our lives when we went to bed that night.

I never shot a gun again.