That February morning back in ’78, the trees in our yard stood like skeletons, as if something had frightened the life out of them. In the eerie stillness, the air heavy with humidity, mourning doves cooed nervously, huddled in the eaves of our cottage. I watched birds move in squads across the gray sky in a ritual of coalescence. Melancholic birdsong was embedded in the distant, cold air, the music faint as I cast breadcrumbs and sunflower seeds on the frozen lawn. Suddenly, a chaos of crows invaded the winter grass. With fierce intensity, they tore at the ground, seeming desperate, as if searching for something they could neither find nor live without.

I had expected the world to be white when I woke up that morning, the ground covered with snow. Another winter nor’easter had been forecasted. With no falling snow, I was relieved to think the meteorologists were wrong, as they had been several times the previous month. Due to those recent inaccuracies, there was widespread skepticism about how much, if any, snow would actually fall that day. Since schools and businesses were going to be open for their usual hours, I wasn’t concerned about the weather as I headed out the door. As a result, I and many others were surprised when light snow began to fall around noon.

After lunch at a Providence cafe, I began walking the four blocks back to the medical clinic where I worked, gazing up at the gray underbellies of clouds. A flurry softly drifted across the faces of old houses, deceptively delicious. My pace quickened as trees ticked back and forth, the wind picking up. Snow like glossy feathers stretched wings over porches and rooftops. By the time I arrived at work, the sidewalks were luxuriously coated, the streets slick. I pushed open the back door of the clinic, brushing off snow that stippled my long brown hair and adorned my coat with pearl epaulets. Thinking we might need to stay after hours if the storm intensified, I had brought a half-gallon of soup from the cafe for my co-workers, and I placed it in the break room.

“Thank you!” a senior nurse said, smiling as she opened the lid, lowering her nose to the aromatic mist.

“When will it end?” I wondered aloud, worrying about the drive home without snow tires in my eight-year-old Chevy. Icy rivulets ran down my forehead. I dabbed my wet face as garlic, ginger, and cinnamon wafted through the air, the hot soup reminding me of my mother’s favorite recipe. As I breathed in deeply, an airy calm settled inside me.

That afternoon, the storm rapidly worsened. The blizzard came without warning—only a winter storm had been forecasted—its sudden ferocity blindsiding us. Radio reports announced that state and city employees would be let out of work early. By midafternoon, the highways were jammed with traffic as 60,000 people flooded the streets of Providence, trying to rush home. The medical clinic where I worked remained open as long as possible, closing at 5 pm. When I left work, five inches of snow had already fallen. At 5:30 pm, with the roads impassable and snow falling at a rate of three inches per hour in extreme winds, the governor declared a state of emergency.

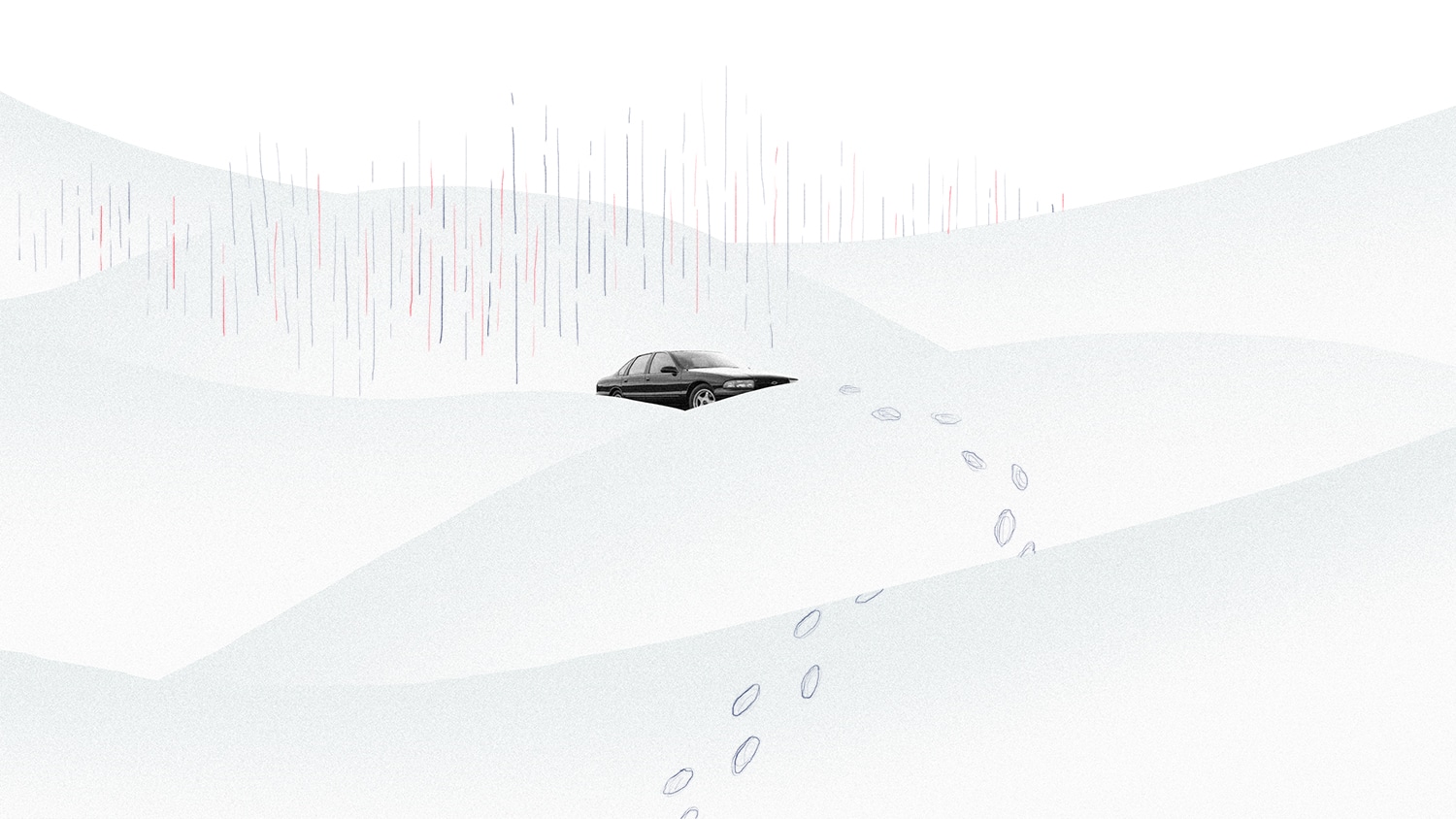

Like an assault, the snow blasted through, bushwhacking the city, choking the streets and shuttering every house. Snow fell and fell with penetrating urgency. After sitting in dead-still traffic for three cold hours, my car was buried in a halo of white. I was enclosed in the compartment’s dark, cold cave, the windshield a solid wall of white. With the gas tank empty and the heater no longer working, I faced a choice: should I stay here and wait for a possible rescue, or try to find my way to an unknown shelter? Either way, I risked freezing to death. Tucking my feet under the car mat, I opened the window slightly as a column of snow collapsed into my lap. I peered into the blustery night at the highway-turned-parking-lot, the city streets immobilized as far as my eyes could see.

Better to take a chance, I thought. It seemed clear that no one would be coming. How could I sit there for hours, maybe days, with no heat? Abandoning my car, I grabbed a folded map to shield my face from the wind, but it quickly blew out of my hand. Without boots or gloves, I walked and walked against the screaming white gusts, seeking safety in downtown Providence. The wind-whipped snow billowed around me, biting and frigid, like little knives slicing my face. The street was a disorienting blur, ghostly and glacial. A frozen expanse—no lights, no businesses open, just deadly, dark quiet. Suddenly, lightning struck terrifying jagged arrows at the corner of a building. I tried to escape the storm’s diabolical frenzy by turning down a street, but realized I was walking in an alley. I grew colder, dragged into the white rip currents of snow, as if exiled from time and space. The ground beneath my numbing feet constantly gave way, slipping beneath me. I was alone in the center of an immense spinning, my body, my life, uprooted, tumbling inside it, engulfed by the rapacious arms of this swirling ghost, pushing and dragging, wanting to knock me down and out and out. A monstrous force stirred within it. Was I walking in circles? What frightened me wasn’t so much the snow, with its incalculable depth and motion, but the angry wind, its strange unearthly howl burrowing inside me. I felt the chill of death, like a cold breath on my neck. Its brightness and suddenness enfolded me as I trudged through foot-high snow, my calves disappearing in the icy mounds, my body numbing, wanting warmth, wanting sleep.

I have to keep moving, I thought. If I rested in one place without moving, if I fell, I’d freeze to death. My heart raced. Was this the spot where I’d fall? I moved slowly, prodding the slippery bog with my frozen feet, heavy as anvils. I lifted them, one in front of the other, losing my equilibrium, as snow encircled me in a blinding cyclone. I can do this. I’ve been through worse. My eyes barely opened slits, I bowed my head against the furious wind, as if pushing against a white-throated beast. I was moving forward, wasn’t I? The alley was a maze of ice mirrors, a dizzying blur. The horizon vanished; the sky turned upside down. Fatigued, my leaden legs buckled under. I stumbled into a snowdrift, feeling almost invisible. Swallowed in the snow-wind turning on itself, I slipped, tumbling all the way to the bottom of a long white slide. My body bowed forward, a blue speck turning to ice. Stay here, the wind seemed to moan, and I sat for just a moment, and then another, as time froze. I don’t know how long I sat there, motionless, looking at the white road before me, as if it were a way to enter paradise. My breaths strung together like a rosary―cold breath in, fast breath out; my lungs were frozen pipes about to burst. I sat frozen in the posture in which I fell, the snow thrashing in mini-whirlwinds, my body being molded into a snow sculpture. Exhausted, I imagined lying down in the strangely comforting snow, letting it possess me.

Something beckoned me—some rousing, distant voice tied to me for all eternity. You’re not a victim. You’re a survivor. Still alive. I won’t leave your side. I struggled to my feet, hauled up by that godsent coil of strength. If only I could see where I was going, I thought, slogging through the snowy peaks and ridges, my spine turning hard as an icicle, ice slicing through my veins. My face rimed with snow, I shivered so much I could barely move my limbs. Was I really alone here? Weren’t there any shelters in this part of the city? I felt short of breath as if I’d been dropped on a mountaintop, the snow gulping oxygen from the air. With each step, I sank deeper and deeper into the snow, which wrapped around me like a mummy. As the numbing cold bore into me, my thoughts drifted to another savage winter night in Providence, a few years earlier. I had almost died then, too.

Suddenly in the whiteout, two lights flashed in the distance, growing larger, brighter, closer. A large, dark mass jerked forward down the narrow alley. Sliding, it slowly careened toward me—a black sedan, spinning its tires and pushing its weight through the heavy snow. Getting its grip, the car moved forward. The driver spotted me, his eyes locking onto my face, my long blue coat. The car stopped, and the window rolled down.

“Get in,” the driver shouted, his voice pushing against the roar of the wind, scattering. I froze as he stared at me, shoving open the heavy door. “Want a ride?”

In the whipping snow, I could barely see his face. He was thirtyish, with longish brown hair, a black faux-fur collar framing his square jawline. Who was this man? Why was he driving down this alley of barricaded doors and broken windows? There were no signs of life, no cars on the streets. Could I trust this stranger?

I froze in a flashback of that other frigid winter night, several years earlier, just a few miles from this spot. The incident was still raw, terrifying. I had left work at 7 pm, walking through a dimly lit hospital parking lot to my car. I was eighteen years old. In the nine-degree temperature, icy winds pierced through me as I started to unlock the car door. Suddenly, a man lunged from the shadows and grabbed me from behind in a chokehold. There was no one in sight except a witness nearby, frantically shouting, “Let go of her! Let go! Stop! I’m calling the police!” But the man was not deterred.

“Get into the car! Open the door!” he shouted, pushing a knife against my throat, his other hand clenching my chest. I fumbled with my car keys, stalling for time, knowing I must not get into my car with him, I must not. “Hurry!” he growled, pressing the cold steel into my skin as the witness kept shouting to release me. Fearing I would never be found if he pushed me into the car, I dropped the keys, but then he dragged me away, through the streets, through the traffic, into the endless night. Somewhere along the way, one of my white shoes fell off.

Kicking up small spumes of snow, I plodded to the black sedan. I had to trust this stranger, I thought. I climbed in and sat close to the door, white-knuckling the warm handle. Please, God, keep me safe.

“Thank you,” I said, shivering.

“Hi, I’m Fred,” he replied, smiling as he spoke, his smile broad and friendly. “It’s some storm,” he remarked.

I looked at him briefly and smiled back.

He had large hands and the rugged features of an outdoorsman. A cloud of unspoken emotions hung in the air, like thick flakes of snow refusing to melt. “Let’s try to get out of here,” he said, cranking up the heat and repositioning the vents.

I sat there, silent and demure, as the warmth poured out, the car’s dark red interior a small reprieve.

Fred drove just one block before the radials became embedded in deep snow, spinning futilely. We could go no farther; the car was stuck in a snowbank. Together, we walked into the raging blizzard, the icy wind pounding my face and bare legs, each footstep encased in snow. Walking in the foot-high snow became increasingly difficult, and I felt I was slowing Fred down, but he held my arm and lifted me when I stumbled, his broad chest shielding me from the wind’s constant battering. Disoriented in the whiteout, I didn’t know where we were going. With each plodding step, I became smaller and smaller, like a tiny, cold seed.

We turned a corner. Icy chips whipped my body at stupefying speeds, stinging my face and thickly clinging to my eyelids. The cold wet seeped into my shoes and through the wool fibers of my coat. The snow changed the color, shape, and weight of what it touched, a white shroud covering everything.

Faint amber light glowed through the stained glass windows of a chapel. I rang the bell several times before a robed man appeared at the door. “Sorry, we’re full,” he replied, lowering his head. Lifting our collars, we trudged our way through the swirling, deserted streets. I thought of my mother, worrying at home, waiting, hoping for my return as she had done on that night years earlier, her daughter missing, kidnapped. The hours spent not knowing, praying—a parent’s worst nightmare.

In the distance, a neon sign flickered in the white haze above a donut shop, shadows moving behind the windows. Fred looked at me as if reading my thoughts, his stocky shoulders lifting beneath his heavy jacket. I paused for a moment, closing my eyes against the wind. “Holding up?” he asked, his face a perfect white mask. I felt it now, relief, as we strode in slow rhythm toward the halo of orange lights. We entered the warm air, shedding puddles of snow, joining a huddle of snow-weary travelers. Our faces thawed into smiles as an elderly man welcomed us with free coffee and donuts, our dinner for the night. Suddenly, a cannon boom of thunder exploded above us. The room grew quiet with a palpable anxiety, the hot liquid jittering in my cup.

After warming up, Fred and I trekked several blocks to the Outlet Company department store, where we were confined to one area: the bedding department and its rows of bare mattresses. The room had the feel of a homeless shelter. Still, I felt fortunate to sleep on a twin bed in a room with fifty other people. As night pressed around us, I slipped a chocolate bar from my pocket that I had bought at the donut shop, sharing it with Fred. I used my coat as a blanket, clutching my purse to my chest in the dim light. That long first night, I could hardly sleep, the wind knocking against the walls, the heat barely on. I got up several times and stood by a large window that overlooked the wide white corridor of the empty street. I pictured my mother sleeping restlessly, getting up to sit by the window, and my father plowing throughout the night, and I prayed for their safety.

Called “the week the state stood still,” the Great Northeast Blizzard of ’78 killed more than one hundred people in New England, including a five-year-old girl ripped from her mother’s arms when their rescue boat capsized and a ten-year-old boy who was found weeks later in a snowbank just three feet from his home. Fourteen people perished on the highway as snow piled high around their cars, trapping poisonous exhaust fumes. Several people trying to seek shelter were found dead in downtown Providence. With record-breaking snow of two to three feet, hurricane-force winds, and snowdrifts as high as twenty-seven feet, the blizzard held a sense of possession over us, like an act of violence or hate. It was a time when we could not see our way out, when we depended upon the mercy of strangers.

Many New Englanders who survived the blizzard experienced a kind of shell shock that spills over to this day. The memory of its terrible force remains like a scar in our collective psyche. When snow begins to fall, a subconscious panic invades, and we brace ourselves against disaster, trying to stave off danger before the snow piles on itself and we fall under its weight. The children may not realize that our hypervigilance is a reaction to the ’78 blizzard trauma. Adults have handed this wariness down to the next generation, as if in reparation for the past when the blizzard struck, blind with rage for thirty-three hours. We won’t be caught off guard again.

Perhaps we are not meant to know why bad things happen, why nature or people behave in menacing, uncontrollable ways. Still, we try to make sense of the incomprehensible, to attribute at least some small meaning to the meaningless, hoping there may be some unknown purpose being served beyond our mortal understanding.

At the Outlet Company the following morning, the heat ticked on amid rows of boots and socks hanging over chairs to dry. Store employees permitted us to take the elevator to another level, where we stood in line to use the pay phone in a far corner of the dark and cavernous floor. A television station located on the top floor broadcast during the blizzard and provided us with blueberry muffins and coffee. As the blizzard raged on that day, people gathered around a small television, sharing stories and playing cards in the bedding department. We heard that plows couldn’t handle the onslaught of snow, that roads and businesses would be closed all week, the city turned into a ghost town. Many of us would be marooned at the Outlet Company for three days, our cars towed off the highway, impounded in a state lot with more than a thousand other stranded cars. It would be two weeks before I saw my Chevy again.

Walking to the restroom with my store-issued toothbrush, I noticed an older woman, pale and fragile as a snowflake, standing alone between tables of linens and lamps. Her hands were clenched, shriveled up in secret folds, her thin arms hanging like flimsy chains. A coffee cup lay on the floor, leaving wet tracks. Something was breaking apart inside her. Still dressed in my nurse’s uniform, I pressed my hand into hers. “I’m fine. Can I go home now?” she mumbled, a tremor in her squalling eyes. I felt her clammy skin and rapid pulse. “Where’s my insulin?” she whispered, leaning close, her hand letting go. Then her legs went weak, and she started to fall. I helped her lie down on a mattress. She was growing further away, spiraling out, as if she were fleeing or falling from the sky. Her papery face became whiter, slacker; her mouth hung open as I alerted the police of her diabetic emergency. A rescue snowmobile was dispatched to transport her to Rhode Island Hospital. There were several other people who needed their medications, too, and I became worried about the possibility of more emergencies.

In the early evening, we were escorted to a large break room for dinner, the air swelling with the resinous smoke of cigarettes. The lights flickered as a thunderous sound shook the windowpanes. We darted from window to window, searching the sky, the way one does when hoping for the sighting of birds or expecting the weather to change. The whirr of monstrous blades from military helicopters crackled the sky. Green airships hovered by the window, the downdraft beating constant and steady into the snow surrounding our ice palace. Memory unsealed, and I was reminded of the helicopter and squad car searchlights several years earlier, the police spotting me late that night, hours after being abducted, brutally beaten, and violated. I remembered myself infinitely hurt, buried in a whiteness without end, beyond words.

The blizzard’s cruel disturbance, its catastrophic violation of our world, like grief or violent crime, had interrupted―no, halted―our lives. I looked around the room of strangers, young and old, wondering how many were coping with other major traumas, not as visible as a broken arm or other physical malady, but their own personal blizzards, now and in deep time, their own silent snow. What stories lay beneath the fixed smiles, carried unseen, like icy seeds growing heavy inside? What burned in the heart of each person; who needed the hand that reaches out, whether it’s taken or not, to keep reaching?

Even now, decades later, everyone in town becomes edgy at the rumor of snow, declaring personal states of emergency, as if something’s breaking or broken. I scan my cupboards for emergency supplies and pack a blanket in the car before joining neighbors in a ritual dash to the market to stock up on milk, bread, and gallons of water. We leave store shelves bare, not trusting even our modern-day forecasters with their supercomputers, so vastly superior to those of the ’70s. My dog Isabella circles me in a full-hearted panic, sensing a large drop in the barometric pressure—“an exploding bomb,” the meteorologist calls it. My dull terror is wedded to hers. “It’ll be fine,” I reassure her, feeling a heaviness in the air. Her head tilts, her eyes rooted in hope, patterning mine. My eyes glance away. Lying on my desk is February’s parole notification, which my eyes blur to read. I tuck it into my purse, waiting for my husband to return home from work, as the sky darkens and a storm threatens to bury the house. Finally, I hear his car in the driveway, the jangle of keys. As I open the door, cold air slaps my face, and I remember the wind’s assault on the night of the blizzard and the night of the attack, how I shivered to stay alive.

The conviction still grows in me that there are godsent moments in life when the right person appears, especially in times of need or danger, for the world can indeed be a dangerous place. These moments, for me, are more than incredible: they are miraculous. I continue to learn what I can endure and what’s important—not the forgetting, but the remembering with peace and being alive in the world again.

On the second morning, Fred and two other men decided to walk across the bridge to their homes seven miles east of Providence. “It’s like going off to Siberia,” Fred marveled, smiling. The three men stocked up on provisions from the Outlet before leaving: candy bars, earmuffs, ski masks, and drinks. “I’ll be back for you tomorrow in a four-wheel drive,” he said gallantly, outfitted for battle.

“That’s nice of you, but I don’t expect you to go through all that trouble. You need to take care of things at home. Just be safe,” I said.

As promised, he returned the next morning. “Get in,” he urged, with a heroic smile.

But there were older people with health problems who needed the ride more urgently, so I declined his offer.

“Thank you for—”

Fred interrupted before I could finish. “How about a real dinner when this is all over?” he asked.

“I’d like that,” I said.

Later that morning, I tied plastic bags over my shoes and walked the three miles to my home alongside many other stranded people, everyone friendly and grateful, the day turned into prayer. Time stood still, as if we had entered a fourth dimension where hope crept back through the shadows, where neighbors connected with neighbors. In the throes of disaster, we were reminded again of what it means to be human. The city was luminous, and we kept walking our way into its difficult beauty. We blazed paths, matching our paces, possessing the earth again. The streets were quiet, except for our home journeying laughter and the sound of our steps crunching the virgin snow. The roads were not plowed, wouldn’t be for another week, the snow so mountainous we walked on the roofs of buried cars jutting up like headstones in a snowy graveyard. I later heard that a man was found dead in his car on one of those city streets, the snow wrapped around it like a cement tomb. The air smelled clean, filled with our warm misting breaths, and the road ahead sparkled irresistibly.

For that moment, all was oddly calm; the snow, forgiven. The winter sun beamed over storefronts and tin sheds, climbing the eastern sky like a red house. Blue sky, blue sky. All ecosystems were resolving. Winter birds, built to withstand migration from pole to pole, were coming back, like us, changed by the weather’s rough mercy. In the hush, I heard birdsong in the distance, the clear rhapsodic notes growing stronger. Strange chirps and songs, different than I knew. I watched sparrows fly free of their snow cages, their bodies glittering as they rose, disappearing into the warmth of the sun. I cried silently as I turned the bend and saw my ice-encrusted white house swallowed in a volcano of snow: the house almost invisible; my mother homebound inside, waiting for me.